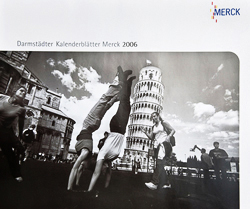

Merck Kalenderblätter

A sounding board for the artistic

Notes on the photographs by Mirko Krizanovic

Roland Held

“As if I were not there” – this is the effect which the photographer Mirko Krizanovic wants his photos to have on the viewer. How are we to understand this somewhat unusual motto which is so different from the usual emphatic individualism and self-confidence that seeks to cultivate an aura of one’s own artistic style? Krizanovic’s thematic focus is on individuals – people of all kinds, whether they are busy crowds who have given themselves to shopping and strolling around in a major German city, or Buddhist monks in a remote monastery in Central Asia, or wounded and deprived crowds of refugees crammed into a camp in a war-torn African country. The photographer is very keen to ensure that the live objects of his interest should be preserved just as they are. His task is not to provoke or arrange, but to wait patiently for the right time when – fleetingly and usually for an extremely brief moment – his lens faces a specific scene. This scene must embody the characteristic features of a wider context and it must do so in a way that is unadulterated, expressive and “focused”. In fact, such a moment would never occur at all if the photographer were perceived by his models in the real world as an aggressive voyeur or a visual parasite. In order to achieve that directness (which is so typical of his best photos) and indeed the intimacy which Krizanovic seeks to obtain, mistrust must have changed at least into toleration or even trust. A distinct sense of discretion is essential, particularly when dealing with other cultures. A photographic intruder is not likely ever to get to the very heart of the matter.

And it is of course important that a photographic journalist should get to the heart of things, and this is the only way to reach the general public at a time when we are flooded with media images and when any informative or thought-provoking elements of a picture are continually sacrificed to the demands of sensationalism. In his book “The Art of Photography”, Walter Koschatzky warns that “Pictures can become sensations. However, it is the job of a photographic reporter to ensure that sensations become pictures.” The title of his reference manual indicates how Mirko Krizynovic succeeds in getting to the heart of things. No matter how topical, moving, amusing or stirring a photograph may be, ultimately it is its formal and artistic qualities that catch our attention and have a lasting effect on us. It starts with the photographer’s self-imposed limitation to black and white and the intervening shades of grey – a decision for a level of abstraction which, depending on the photograph, can suggest either sobriety or magic.

Thanks to the backlighting, milkily filtered true highly complex inside walls and a roof, the bazaar in Kundus and the selective focus on some of its visitors give the additional impression of a place from Arabian Nights. although Afghanistan is known to be far from peaceful, let alone prosperous, Mirko Krizanovic nevertheless travelled there last year and did not just visit sensible and supposedly secure places. In the same way, he had often travelled to the successor sates of Yugoslavia, torn apart by civil war, and to the republics of the former Soviet Union with their many domestic crises and adjustment problems. However, unlike some of his infamous colleagues – “camera soldiers” such as Robert Capa and James Nachtwey – he does not actively look for danger. His photographs are sufficiently convincing even without the smell of blood or cold sweat. The element of humanist engagement in his photos is often triggered by something totally undramatic, as we can see in our selection of twelve photos for the 2006 Merck Calendar. Two examples will illustrate this point: the relaxed, yet wide-awake friendliness of the two tradeswomen in Freetown, Sierra Leone, as they interact with each other while carrying their goods on their heads; and the caring attention with which the woman on a coach to Casablanca lets her henna-tattooed hand rest on the head of her sleeping child. In both cases, the photographer concentrated quite specifically on his subject by focusing on one particular detail. Yet it is also worth noting how much is expressed through hands and eyes and through the directions of people’s gestures and glances! Small things which should be understood throughout the world and without any comment …

The last picture, with its contrast between the mother in her traditional Berber costume and her child with its flashy western-style shirt and trousers, illustrates an artistic strategy that Mirko Krizanovic loves to use in his photography: contrast through content. We all know that black-and-white photography is ideal for making the most of light vs. dark and sharp vs. blurred. Krizanovic uses this technique with masterly expertise. Take for instance the two Argentinean tango dancers charging forward dynamically into the blackness of the stage, or the German female chimney sweep whose silhouette stands out so strikingly against the sky above the oblique roof of the house. Sometimes, however, the inherent contrasts within the objects themselves (caused by their origin in a specific culture, time, etc.) are clear indications of a clash between heterogeneous habitats. The shooting gallery in Havana, with its corrugated iron roof, for instance, seems to stands out like a sore thumb among the sophisticated architecture of the arcades, and the scene therefore requires no words as it highlights both the colourful character of Caribbean communism and the wretched state of Cuba’s economy. Elsewhere the photographer confronts different levels of reality and expectations through photographic effects that cause us to smile – for instance, the encounter between a bronze statue on a plinth an a man with a suitcase outside Federal Hall in Washington. Or the picture-within-picture theme of the renovation work before an exhibition of the baroque painter Guido Reni at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, where the photographer links together two totally opposite views of what art is all about!

To ensure the right camera settings in the right place and at the right time, a photographic journalist needs more than a mixture of intuition, experience and that indispensable bit of sheer luck. An expressive photograph also requires a special mindset on the part of the photographer. “I’ve often visited places where my colleagues don’t go,” says Mirko Krizanovic, referring to his trips to distant countries. He feels it is important to walk about and thoroughly test different locations. One result is his photo of the acrobat Philippe Petit walking across a tightrope on Frankfurt Cathedral in 1994, a photo that was taken with a telephoto lens, not from the northern bank but from the southern bank of the river Main. This was, incidentally Krizanovic’s first work as a freelance photographer, after eight years with Germany’s daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, where the young photographer had been given encouragement, solidarity and valuable ideas by Barbara Klemm and Wolfgang Haut. This photo of the tightrope walker shows Mirko Krizanovic as an artist who, again, is quite cautious in his use of formal elements: in the composition of the photo, which seems extremely imbalanced at first, Krizanovic uses the tiny, frail figure of the tightrope walker as a counterpart to the enormous building, while at the same time benefiting from the tight downwardly diagonal stabilizer ropes with their acute angles that seem like a response to the mediaeval turrets and pinnacles of the cathedral. “You can’t just compose something out of the blue, there has to be some necessity; neither is it possible to separate content from form,” said Henri Cartier-Bresson, the grand master of 20th century photography and advocate of the “decisive moment”. On this point and also on other essential issues of photography, Cartier-Bresson’s views largely coincided with Krizanovic’s who, age-wise, could quite easily have been his grand son. Both shared a reluctance to be too “arty” in their approach. In fact, the word “art” never occurs anywhere in Mirko Krizanovic’s career as a photographic journalist. The photographic series he brought home for selection an evaluation, taken both in his own country and abroad, are undoubtedly first-hand documents. Nevertheless, as we showed in our analysis of a small number of examples, his artistic eye is quite unmistakable. It is therefore legitimate to say that the documentary character of Krizanovic’s work is not a limitation but a sounding board for the artistic.